Needham–Schroeder protocol

The term Needham–Schroeder protocol can refer to one of two communication protocols intended for use over an insecure network, both proposed by Roger Needham and Michael Schroeder.[1] These are:

- The Needham–Schroeder Symmetric Key Protocol is based on a symmetric encryption algorithm. It forms the basis for the Kerberos protocol. This protocol aims to establish a session key between two parties on a network, typically to protect further communication.

- The Needham–Schroeder Public-Key Protocol, based on public-key cryptography. This protocol is intended to provide mutual authentication between two parties communicating on a network, but in its proposed form is insecure.

Contents |

The symmetric protocol

Here, Alice (A) initiates the communication to Bob (B). S is a server trusted by both parties. In the communication:

- A and B are identities of Alice and Bob respectively

- KAS is a symmetric key known only to A and S

- KBS is a symmetric key known only to B and S

- NA and NB are nonces generated by A and B respectively

- KAB is a symmetric, generated key, which will be the session key of the session between A and B

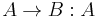

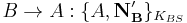

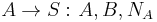

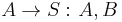

The protocol can be specified as follows in security protocol notation:

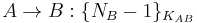

- Alice sends a message to the server identifying herself and Bob, telling the server she wants to communicate with Bob.

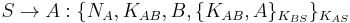

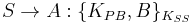

- The server generates

and sends back to Alice a copy encrypted under

and sends back to Alice a copy encrypted under  for Alice to forward to Bob and also a copy for Alice. Since Alice may be requesting keys for several different people, the nonce assures Alice that the message is fresh and that the server is replying to that particular message and the inclusion of Bob's name tells Alice who she is to share this key with.

for Alice to forward to Bob and also a copy for Alice. Since Alice may be requesting keys for several different people, the nonce assures Alice that the message is fresh and that the server is replying to that particular message and the inclusion of Bob's name tells Alice who she is to share this key with.

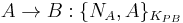

- Alice forwards the key to Bob who can decrypt it with the key he shares with the server, thus authenticating the data.

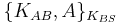

- Bob sends Alice a nonce encrypted under

to show that he has the key.

to show that he has the key.

- Alice performs a simple operation on the nonce, re-encrypts it and sends it back verifying that she is still alive and that she holds the key.

Attacks on the protocol

The protocol is vulnerable to a replay attack (as identified by Denning and Sacco[2]). If an attacker uses an older, compromised value for KAB, he can then replay the message  to Bob, who will accept it, being unable to tell that the key is not fresh.

to Bob, who will accept it, being unable to tell that the key is not fresh.

Fixing the attack

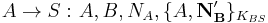

This flaw is fixed in the Kerberos protocol by the inclusion of a timestamp. It can also be fixed with the use of nonces as described below.[3] At the beginning of the protocol:

- Alice sends to Bob a request.

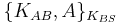

- Bob responds with a nonce encrypted under his key with the Server.

- Alice sends a message to the server identifying herself and Bob, telling the server she wants to communicate with Bob.

- Note the inclusion of the nonce.

The protocol then continues as described through the final three steps as described in the original protocol above. Note that  is a different nonce from

is a different nonce from  .The inclusion of this new nonce prevents the replaying of a compromised version of

.The inclusion of this new nonce prevents the replaying of a compromised version of  since such a message would need to be of the form

since such a message would need to be of the form  which the attacker can't forge since she does not have

which the attacker can't forge since she does not have  .

.

The public-key protocol

This assumes the use of a public-key encryption algorithm.

Here, Alice (A) and Bob (B) use a trusted server (S) to distribute public keys on request. These keys are:

- KPA and KSA, respectively public and private halves of an encryption key-pair belonging to A

- KPB and KSB, similar belonging to B

- KPS and KSS, similar belonging to S. (Note this has the property that KSS is used to encrypt and KPS to decrypt).

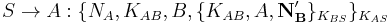

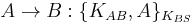

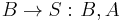

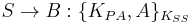

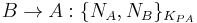

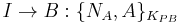

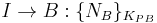

The protocol runs as follows:

- A requests B's public keys from S

- S responds with public key KPB alongside B's identity, signed by the server for authentication purposes.

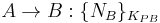

- A invents NA and sends it to B.

- B requests A's public keys.

- Server responds.

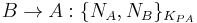

- B invents NB, and sends it to A along with NA to prove ability to decrypt with KSB.

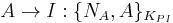

- A confirms NB to B, to prove ability to decrypt with KSA

At the end of the protocol, A and B know each other's identities, and know both NA and NB. These nonces are not known to eavesdroppers.

An attack on the protocol

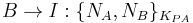

Unfortunately, this protocol is vulnerable to a man-in-the-middle attack. If an impostor I can persuade A to initiate a session with him, he can relay the messages to B and convince B that he is communicating with A.

Ignoring the traffic to and from S, which is unchanged, the attack runs as follows:

- A sends NA to I, who decrypts the message with KSI

- I relays the message to B, pretending that A is communicating

- B sends NB

- I relays it to A

- A decrypts NB and confirms it to I, who learns it

- I re-encrypts NB, and convinces B that he's decrypted it

At the end of the attack, B falsely believes that A is communicating with him, and that NA and NB are known only to A and B.

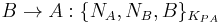

Fixing the man-in-the-middle attack

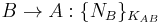

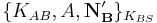

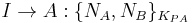

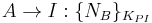

The attack was first described in a 1995 paper by Gavin Lowe.[4] The paper also describes a fixed version of the scheme, referred to as the Needham-Schroeder-Lowe protocol. The fix involves the modification of message six, that is we replace:

with the fixed version:

See also

References

- ^ Needham, Roger; Schroeder, Michael (December 1978). "Using encryption for authentication in large networks of computers.". Communications of the ACM 21 (12): 993–999. doi:10.1145/359657.359659

- ^ Denning, Dorothy E.; Sacco, Giovanni Maria (1981). "Timestamps in key distributed protocols". Communication of the ACM 24 (8): 533–535. doi:10.1145/358722.358740.

- ^ Needham, R. M.; Schroeder, M. D. (1987). "Authentication revisited". ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review 21 (1): 7. doi:10.1145/24592.24593.

- ^ Lowe, Gavin (November 1995). "An attack on the Needham-Schroeder public key authentication protocol.". Information Processing Letters 56 (3): 131–136. doi:10.1016/0020-0190(95)00144-2. http://web.comlab.ox.ac.uk/oucl/work/gavin.lowe/Security/Papers/NSPKP.ps. Retrieved 2008-04-17

External links

- http://www.lsv.ens-cachan.fr/spore/nspk.html - description of the Public-key protocol

- http://www.lsv.ens-cachan.fr/spore/nssk.html - the Symmetric-key protocol

- http://www.lsv.ens-cachan.fr/spore/nspkLowe.html - the public-key protocol amended by Lowe